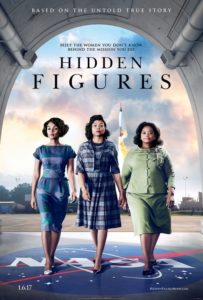

Real Hidden Figures

If you haven’t seen the movie, Hidden Figures, you should. It is a true story, a tale of a group of African-American women hired at the dawn of NASA for their superior mathematical skills. It reminded me of so many things at NASA.

People ask: do you miss flying in space? Well, yes, a little. Mostly, I miss the fine people. Like the people in the movie, they weren’t all perfect, but they learned from their mistakes and always tried to improve.

It was part of the culture.

I remember an episode that taught me some important lessons.

I had been assigned to help verify the computer programs that ran the Space Shuttle. I found an unrecognized glitch that could have been catastrophic. I reported it proudly to the Chief of the Astronaut Office. He listened patiently and then, he was silent. After an uncomfortable moment, he said “Okay, good job. And what should we do about it?” Taken aback, I sputtered that I wasn’t sure.

“Go find out. Your job here is not only to bring me problems but also to bring me solutions.”

When I arrived at the Johnson Space Center in 1978, with the exception of our excellent secretaries and the wonderful ladies in the cafeteria, it was a man’s world. As time went by, more women pursued science and engineering degrees in college and came to work at NASA. They rapidly proved themselves – sometimes working harder than their male counterparts. We all became friends and allies. Ten years after I arrived, the workplace had become more diverse in both gender and race – thousands pulling together execute exciting missions with pride.

There were women Flight Directors in Mission Control, tough and intelligent, living by the mantra of their boss, Gene Kranz – “Failure is not an option.” There were the female voices of trainers on consoles at our simulators – so calm and patient with our frequent mistakes when our training began, so proud of our eventual mastery. The first female Space Shuttle pilot’s voice was beamed from orbit in 1995.

The movie portrays John Glenn perfectly, which made me proud to have known him. His polite and inclusive bearing reflected the demeanor of the many astronauts I worked with in my day. All of us frequently worked late at the office. The cleaning crews came in after hours, and we got to know the people who tidied up our offices. A film crew asked one of them: “Do you really know Astronauts?”

She said, “Why, yes, sir. They know my name – and they have signed autographs for my kids.”

We assured them they were making their contribution to the space program – and that we hoped their kids would be the astronauts of the future.

In the movie, a woman whose brilliance as a mathematician had not yet been recognized, identified two problems where she worked.

Go…

Go see the movie to see her solution.

– Rhea

We’d love to add you to our email list.

If you have not yet signed up, please do so by clicking here.

Your story reminds me of one I was told by that wonderful gentleman Gunther Wendt. He was a signer at one of the autograph shows, and it astounded him when one attendee ignored the more famous signers and came just to see him. The visitor explained that he’d grown up with Gunther’s name spoken proudly in the house because his dad had worked at KSC–as a janitor. Gunther made sure to give all the custodians VIP tours of the launch complex, and that display of respect made him a hero to this show attendee. He was there just to say thank you to the man his father admires so much.

Gunther was deeply moved, but he was quick to make sure I knew that his gesture was nothing special–in that unforgettable accent he gruffly insisted, “Of course we welcomed the custodians–they were our colleagues! Of course we wanted them to know we respected them! We all worked! Those men worked! I had generals and Congressmen on the pad all de time and those bastards did nothing! But the men with the brooms–they were like us!”