Can You Hear Me Now?

Ground Station Antenna

Imagine feeling that you are lost in space. In the early days of spaceflight, Mission Control couldn’t always talk to the Astronauts, leaving them feeling out of touch with Earth. The silence must have felt eerie.

Communication in those days had to be sent and received by ground stations which were part of the NASA Spacecraft Tracking and Data Acquisition Network. This network consisted of stations spread around the globe but there were gaps between stations.

When I got to NASA in 1978, I recall looking at the huge map on the front wall in Mission Control. It showed where the Shuttle was in its orbit and path around the world. The map also showed areas over the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean where there could be no communications with the ground. These areas were marked with the letters LOS and AOS which stood for Loss of Signal and Acquisition of Signal.

Mission Control Map

When I began to work in Mission Control, I had to remember that we couldn’t talk to the crew during those times. We hurried to get important messages up to them before LOS and had to wait patiently for their reply at AOS. When they were in this “dead zone” we had to guess what the crew would be doing and what they were most likely to want to know when we could communicate with them again. There was always the fear that something dire had happened during these times and a relief when we heard voices out of the void.

Plasma shield during reentry

Another problem was that the Shuttle could not communicate with the ground at all during reentry because of the heat of the plasma on the belly of the vehicle. It was nerve wracking not to have information on the vehicle during this fiery drop into the atmosphere.

TDRS deployment

NASA understood that communicating through ground stations with such large gaps was not optimal and they began to study how to place space-based communication satellites in high orbit which could relay messages from the ground down to vehicles in orbit. These satellites were called Tracking and Data Relay Satellites or TDRS. The first, TDRS-1 was launched on STS-6 in 1983. Sadly, the second of these satellites was lost in the Challenger accident in 1986. The next was launched on STS-26, the Return to Flight mission.

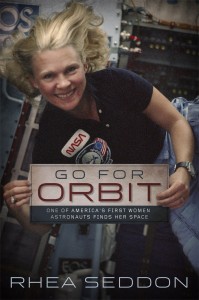

On my husband’s second flight, STS-27, the crew could communicate though the Shuttle’s upper antennas with the TDRS. It was the first flight to have good communication with the ground all the way though reentry. That was a wonderful improvement for those of us in Mission Control who were anxiously awaiting their calls that everything was going well on their red-hot ride home. —Rhea

To receive Rhea’s blog to your inbox, simply sign up here, and we will see you next month!

Follow me on Facebook and LinkedIn.

Subscribe to Dr. Seddon’s YouTube Channel here!

Not too many of the early astronauts who did CAPCOM in the Waimea Tracking Station on the Hawaiian island of Kauai seemed to complain too much about that location, but few were that exotic. It doesn’t look like Waimea was used much beyond the early Gemini flights. During Apollo the ultimate LOS area was on lunar farside, which created many occasions of comm blackout during critical mission steps like lunar orbit insertion or Earth return engine burns. Perhaps a lunar comm relay satellite or Lunar Gateway will eliminate this comm out area during Artemis.